Jonathan Clark Fine Books

Art and Architecture

NICHOLAS HAWKSMOOR'S copy of Daniel KING

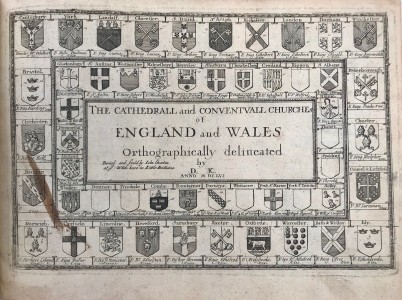

The Cathedrall and Conventvall Churches of England and Wales Orthographically delineated by D. K. MDCLVI.

London, Printed and Sould by Iohn Overton at ye White horse in Little Brittaine, 1656-1672.

Small oblong folio (230 x 305 mm). Bound in late nineteenth century quarter brown calf over cloth-covered boards, red calf and gilt-lettered label to the spine, marbled endpapers, all edges red; 78 etched plates printed on 77 leaves, all but two of the plates (16,17) interleaved with blank sheets, several of which bear drawings in graphite, or graphite, pen and ink (see below), the plates numbered thus: etched title-page (as above), [unnumbered], 2, [unnumbered], 5-13, 130, 15-33, [unnumbered], 35-40 (pls. 37 and 38 printed on one sheet), etched title-page (Monasticum Anglicanum), 41, [unnumbered], 43-46, 25, 34, 32, 50, [unnumbered], 52, 53, 282, 55, 59-62, [unnumbered], 64, 65, [unnumbered], [unnumbered], 68-81; plate 16, showing a plan of Westminster Abbey, titled ‘The Ichonography of the Church of Westminster’, bears an ink correction in Hawksmoor’s hand to the west wall of the south transept and the adjacent cloister, repositioning the wall to where it is actually sited, i.e. on the same axis as the west arcade in the north transept, rather than on the same axis as the external west wall of the north transept as shown in the etched plate; plate 25 illustrating the ‘South Prospect of the Cathedrall Church of Ely’ bears faint traces of pencil additions to the lantern above the crossing of the nave; plate 69 showing the ‘West Prospect of ye Cathedral Church of Lincoln’ is inscribed in ink in Hawksmoor’s hand, just outside the platemark with the word ‘Rose’; old repair to the the verso of plate illustrating the plan of Canterbury Cathedral, strengthening to the fore-edges of the plates illustrating the north prospects of Ely and Worcester Cathedrals, the south prospects of Tewkesbury Abbey and Beverley Minster, the north prospect of Exeter Cathedral, the south prospect of Norwich Cathedral, Comb[e Abbey], and the south prospect of Lincoln Cathedral, old paper repair to one of the folds in the plate illustrating the north prospect of Salisbury Cathedral, occasional light age-toning, one or two old ink marks, otherwise a clean copy.

Provenance: 1. Nicholas Hawksmoor (1661-1736), architect. 2. George Winn, with his late nineteenth- century engraved armorial bookplate to the front pastedown.

Comments on notes and drawings by Nicholas Hawksmoor in his copy of Daniel King’s The Cathedrals and Conventual Churches of England and Wales Orthogonally Delineated (London 1656) by Dr. Gordon Higgott FSA.

As noted in the collation the present volume is interleaved throughout with blank sheets matching the dimensions of the etched plates. Two of these sheets, and a further smaller sheet, secured by wax to the verso of the second of these sheets, bear survey notes and sketches made at St Alban’s Abbey on the 10th, 20th and 22nd of July 1720 in the company of a ‘William Carter of St Albans’. These are important records of Hawksmoor’s work in church architecture at this time and are largely self-explanatory. It is likely that these drawings were made in preparation for an engraved plate published the following year, showing a prospect of the north front of the abbey and the ruins of Roman Verulamium beyond, taken from the top of the clock tower in the centre of the town. Proceeds from the sale of the engravings were intended to raise funds for the restoration of the fabric of the abbey which, since the Dissolution, had fallen into disrepair.

The following comments are on three items that are less easily understood: a pencil sketch of a cupola on Daniel King’s etching of the south prospect of Beverley Minster, a plan of a palace on a separate sheet, and a list of prints on a sketch of part of the chapel of the Virgin Mary at the east end of St Albans Abbey.

Sketch of tower and cupola on the crossing of Daniel King’s etched plate of the south prospect of Beverley Minster.

Hawksmoor was Surveyor at Beverley Minster from 1716 to 1720 but his work there is poorly documented. See Gordon Higgott, ‘Sir Christopher Wren’s failed project for a crossing tower and spire at Westminster Abbey’, The Burlington Magazine, vol. 161 (January 2019), pp. 53–4 and notes 58, 60). His previously unknown involvement at St Alban’s Abbey in July 1720 was presumably a result of his four years’ earlier experience at Beverley and may have coincided with the end of his tenure there.

Sketched on King’s etching of the south prospect of Beverley Minster in the volume is a version of the cupola that Hawksmoor designed for the crossing of the Minster soon after his appointment in 1716. An engraving of the north prospect of Beverley Minster in about 1717 shows Hawksmoor’s proposal as then conceived (Higgott 2019, Fig. 17). A low square tower carries an ogival leaded cupola and the parapet of the tower rises only slightly higher than the ridge of the roof. It was built in brick, faced with stone, in 1721–22, and demolished in 1824. There is no other visual record of the tower and cupola (See Ivan Hall, ‘The first Georgian restoration of Beverley Minster’, The Georgian Group Journal, 1993, pp. 13-31, and N. Pevsner and R. Deane, The Buildings of England: Yorkshire: York and the East Riding, London, 1995, p. 286). Writing in 1735 to the Dean of Westminster about his tower and cupola at Beverley, Hawksmoor cites the c.1717 north prospect as a record of what was built: ‘you will see how we finished the Middle Lantern, which was Left at the hight of the Gutter [i.e. the base of the roof]; but we raised it as high as our mon[e]y would Reach, and covered it in form of a Gothic Cupola’ (see Downes, Hawksmoor, 1979, p, 260; Higgott 2019, note 60). Hawksmoor’s sketch on Daniel King’s south prospect of Beverley Minster is the only known design from his hand for this lost feature. It may have been drawn in 1720, at the same time as the notes about St Alban’s in this volume, that is, before the work began on the tower and cupola at Beverley. It shows the tower considerably higher than shown in the north prospect of c. 1717. Thus it represents Hawksmoor’s unrealised intention for a larger tower and cupola over the crossing at Beverley, either in 1720, before work began there, or when he first considered this addition in 1716.

Plan of a palatial building, probably for rebuilding St James’s Palace, c. 1715-18.

This previously unknown scheme incorporates, on the right side of a central circular ambulatory, two chapels connected to each other by a corridor and circular hall. The left of these is similar in plan to Jones’s Queen’s Chapel at St James’s Palace (1623-27), but appears to be a scheme for its reconstruction, wider and longer than the existing Chapel, and now part of a grand palatial complex with a long gallery building at the top of the plan. The existing Queen’s Chapel is 84 ft long by 25 ft wide (see H.M. Colvin (ed.), The History of the King’s Works Volume V (1660–1782) (London, 1976), p. 246, Fig. 21). In this palatial plan, judging by the inscribed internal lengths of ‘20’ and ‘70’ feet (not including wall thicknesses), the chapel would have had a similar internal arrangement but would have been around 105 feet long and 40 feet wide. A corresponding rectangular building with internal apses and columns, placed on the opposite side of the circular ambulatory, is probably a Council Chamber. Both Chapel and Council Chamber would have been entered from the west through four-column entry halls. The most plausible explanation is that the plan is for rebuilding the eastern part of St James’s Palace, with Inigo Jones’s Queen’s Chapel retained or rebuilt near its centre. St James’s Park would be on the right side of the plan, to the south. Marlborough House is not shown to the east of St James’s Palace at the top of the drawing, and would presumably have been demolished to make way for this scheme. The whole complex would have been entered through a ten-column dipteral portico on the west side, giving access to an apse-ended hall at the centre of a long gallery range that is roughly an equivalent to the gallery range at the top of the plan.

The plan is datable to the period when Hawksmoor was Clerk of Works at Whitehall, Westminster and St James’s Palaces from 1715 to 1718. (see King’s Works V, pp. 52–3, 239–42; and the entry on Nicholas Hawksmoor in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). These were important positions, for St James’s Palace was then the principal royal residence in Britain, and remained so throughout the reigns of George I and II. After the fire at Whitehall Palace in 1698–99 Hawksmoor had prepared several schemes for rebuilding on a vast scale. The idea of reconstructing a royal palace in Whitehall was not formally abandoned under Queen Anne and gained brief momentum soon after the accession of King George I in 1714. In about 1718–19 an unidentified architect working under the new Surveyor William Benson drew up a scheme for the rebuilding St James’s Palace. This is only known from three drawings, not previously discussed in print. See the entries in my online catalogue of English Baroque Drawings at the Soane, completed in 2009: St James's Palace and Park, London

In 1715–18 Hawksmoor produced a scheme for a new Doric colonnade on the west side of the Great Court at St James’s Palace (Geraghty, Architectural Drawings of Sir Christopher Wren, 2007, cat. nos. 244, 245; Downes, Hawksmoor, 1979, cat. nos. 311–12, p. 280, where dated c.1715-18). The rebuilding scheme in the Daniel King volume – if indeed for St James’s Palace – applies this architectural language of classical colonnades and galleries across the palace as a whole. The style of numbering on the plan is consistent with Hawksmoor’s hand in the later 1710s and is a close match for that in his survey drawings of St Albans Abbey.

List of twenty plates beneath Hawksmoor’s sketch of the east window of the chapel of St Mary the Virgin at St Albans, dated 22 July 1720.

Dating probably to 1720, the list in a pencil medium (black chalk or graphite) and in pen and brown ink on the lower left side of the drawing is an important record of prints in Hawksmoor’s collection at that time. The use of two media, with ink added to the pencil, indicates an evolving list, begun at the time the sketch was drawn and added to afterwards. It may be evidence of Hawksmoor’s involvement in the gathering of material for the Wren family memoir, Parentalia, on which Wren and his son Christopher began work in 1719 (see Lisa Jardine, On a Grander Scale: The Outstanding Career of Sir Christopher Wren, London, 2002, pp. 476–77). The note at the end, ‘Plates in, all – 20 no.’ refers to the total marked with numbers, and not the two marked with dots (see below). The list may be connected with plates that eventually appeared in Parentalia in 1750:

‘Tem Pacis 1’ is the Temple of Peace and ‘Mars Ultor 1’ the Temple of Mars Ultor in Rome. Both buildings are described in Wren’s Tract IV in Parentalia, pp. 359–66

‘A Plan of the Temple of Mars Ultor’ is printed on p. 364 of Parentalia.

‘Sarum .’ is presumably Salisbury Cathedral, where Wren advised on strengthening works to the tower and spire in 1668. There is a dot rather than a ‘1’ after the name, indicating that one was needed but that no plate was then available. Parentalia includes a single view of Salisbury Cathedral, a south-west prospect by J. Harris, facing p. 303.

Similarly, there is a dot after ‘Westminster’, suggesting an item not yet available. In 1720 Wren was Surveyor at Westminster Abbey and had prepared a scheme for a new crossing tower and spire. But the only printed view of the Abbey of any quality at that time was Hollar’s north prospect of 1754. The print illustrating Wren’s scheme for a tower and spire is opposite p. 295 in Parentalia. It dates from the late 1730s, after work had begun on Hawksmoor’s west towers, illustrating in the view, but not as finally completed at the top in 1745.

The ‘Theatre’ of which three plates are listed is presumably Wren’s Sheldonian. These three could be Loggan’s two engravings of the exterior in 1669 (Wren Society, vol. V. pls II and III) and the plan of the roof published by Robert Plot in Natural History of Oxford-shire in 1677 (see Anthony Geraghty, The Sheldonian Theatre, New Haven and London, 2013, pl. 50). In Parentalia a revised version of Loggan’s view of the main entrance is reproduced opposite p. 335, and two plates of the roof trusses and the roof plan (derived in part from Plot’s engraving in 1677) are placed between pp. 336 and 337, making three in total.

The three plates of ‘old Paul’s’ are probably from Hollar’s etchings of the plan and exterior views of the cathedral published in Dugdale’s History of St Paul’s Cathedral in 1658. Surprisingly, Parentalia did not reproduce any views of the old cathedral.

‘London old and new’ are likely to be the two plates in Parentalia showing London ‘about the year 1560’ (facing p. 267) and of Wren’s rebuilding scheme after the Great Fire in 1666 (facing p. 268).

The ‘column’ with a bracketed {1} is probably a reference to a plate soon afterwards in preparation: the engraving by Hulsbergh in 1723 of the Monument to the Great Fire, the ‘Columna Londinensis’, designed by Robert Hooke with advice from Wren. Hulsbergh’s engraving was made from a drawing by Hawksmoor (‘N: Hawksmoor Delin. 1723). See The Wren Society, vol. 18 (1941), pl. XVIII. No print of the Monument appears in Parentalia.

‘New Pauls 5’ would be the engravings of the cathedral prepared between about 1686 and 1710, with which Hawksmoor had been closely involved as a draughtsman. These include Jan Kip’s plan and north prospect of 1701, a long section first engraving in c.1687 modified in the 1710s, Simon Gribelin’s west elevation of 1702, and his section through the transept and crossing of c.1695; and Thomas Trevitt’s north-west prospect of 1710 (see The Wren Society, vol. 14, respectively plates VI, X, IX, XII, XXII, XLII). Different versions of some of these prints were used in the account of St Paul’s in Parentalia.

‘Mausol – 4’ is the most intriguing entry. It may refer to prints that Hawksmoor intended to prepare to illustrate a reconstruction of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus. In c.1711–14 he drew four designs of buildings inspired by the Mausoleum (Geraghty 2007, cat. nos. 175–78) and he later drew a reconstruction of the mausoleum for publication in print-form to illustrate Wren’s account ‘Of the Sepulchre of Mausolus King of Caria’ at the end of his Tract IV, published on pp. 367–8 of Parentalia. This drawing, in his very late hand, is pasted to the last page of the manuscript known as ‘Tract V, “Discourse on Architecture”’ in the RIBA Heirloom copy of Parentalia, where it faces p. 367 (see Gregg Press facsimile of this edition, 1965). No engraving of the mausoleum was prepared, for the section at the end of Tract IV concludes with the note, ‘The Plate of the above is omitted, on account of the Drawing being imperfect’. We are therefore left with this intriguing reference in 1720 or soon after to four plates of a mausoleum in Hawksmoor’s possession.

Stock number: 1391